Lord Bracknell

On fire

Guilty as hell for quite a lot of crimes, but not this one, it would seem.

George Davis in court 40 years after robbery that sent him to jail

Judges will finally decide whether 'George Davis Is Innocent OK' as they look again at notorious miscarriage of justice case

Duncan Campbell

The Guardian, Thursday 24 February 2011

Cricket fans arriving at Headingley in Leeds in August 1975 were anticipating a thrilling finish to the third Ashes Test. Instead, they were greeted by a puzzling message daubed in whitewash on the walls at the entrance to the ground. "Sorry, it had to [be] done," it read. "Free George Davis."

To most of those hoping to see England whip through the Aussie tailenders, the name may have meant nothing. But George Davis was soon to become one of the best-known prisoners in Britain.

Inside Headingley that morning, ground staff were already surveying the damage. Chunks of earth had been dug from the pitch and oil spread across it. The match was abandoned and with it England's hopes of a win. But for Davis and his supporters, the bold stunt was one more step towards his freedom.

This week, nearly 40 years after the robbery that sent him to jail, Davis, now 69, finally has his day in court.

Three appeal court judges in London will decide, following a two-day hearing which concludes on Thursday, whether or not they agree that, in the words of countless badges, banners and T-shirts of the time, "George Davis Is Innocent OK."

Davis, a minicab driver, was already in the second year of a 20-year sentence for his alleged part in a robbery at the London Electricity Board in Ilford, Essex, in April 1974. He had been jailed at the Old Bailey for robbery and wounding with intent to resist arrest. His initial appeal was turned down although the sentence was reduced to 17 years.

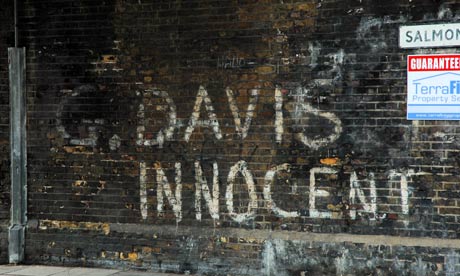

His friends, family and wife, Rose, then embarked on perhaps the most spectacular campaign ever mounted to expose a miscarriage of justice. "George Davis Is Innocent OK" was painted on walls and bridges all across the East End – some of the graffiti survives to this day.

In order to catch the attention of the media, Peter Chappell, one of Davis's loyal friends, drove his lorry up the steps of or into the front doors of half of the country's national newspapers. Other supporters chained themselves across Fleet Street.

In case anyone wasn't paying attention, Chappell then drove into the gates of Buckingham Palace, all the time proclaiming that Davis was an innocent man. The band Sham 69 recorded a song of the slogan. When it seemed that Davis might still have to serve his sentence, Chappell and Rose's brother, Colin, climbed into Headingley by night and dug up the pitch. Now the campaign became known all over the world. "Needs must when the devil drives," became Rose's motto.

Eventually, the campaign paid off. The home secretary, Roy Jenkins, asked for a review of the case. In May, 1976, Davis was released under the royal prerogative on Jenkins's advice.

Although the conviction itself was not quashed – hence this week's appeal – the release was a significant achievement in that there were then no obvious avenues for victims of miscarriages of justice to explore. The campaign became a template for others who had been wrongly convicted but had given up on their own cases. Davis himself was greeted as a conquering hero on his release; a famous photo of the time shows him with Rose in a joyful crush at Waterloo station. The laws on identification evidence have since been changed, not least as a result of the case and the issues it raised.

The euphoria was short-lived. Only 18 months after his release, Davis was caught red-handed robbing the Bank of Cyprus in Holloway, north London.

It was a heavy blow to Rose. As she recounted in her memoir, The Wars of Rosie: "I felt gutted for all those people who had helped us."

This time Davis was jailed for 15 years, reduced to 11 on appeal. No campaign followed the conviction. Rose died of cancer at the age of 67 in 2009.

This week's appeal, in front of Lord Justice Hughes, Mr Justice Henriques and Mrs Justice Macur, comes in response to a referral by the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), the body set up in 1997, partly in response to the many miscarriage of justice campaigns inspired by the Davis case.

In announcing the grounds for the appeal last year, a spokesperson for the CCRC said that "several complaints about the Metropolitan police's investigation of the LEB robbery prompted an investigation by Detective Chief Superintendent Moulder, of Hertfordshire police.

"The reasons for the referral are that the commission believes that non-disclosure at the time of Mr Davis's original trial of information which may have assisted the defence and/or undermined the prosecution's case at trial, as well as evidence subsequently obtained by the Moulder investigation and, more recently by the CCRC, raise a real possibility that the court may quash the conviction."

Davis hopes that the case will reassure all his supporters from those years ago that their efforts were justified. Now remarried, to a police officer's daughter, he has been working as a driver again.

There is still no shortage of people in prison desperately trying to grab the attention of the public and the media about their cases. Since the CCRC was set up, more than 13,000 people have asked them to re-examine their cases, of which 310 convictions have been quashed and 401 are currently under review. Some campaigns, like that of Kevin Lane, jailed for the 1994 murder in Hertfordshire of Robert Magill and still trying to have his case referred back to the court of appeal, have their own sophisticated websites.

The Guardian's own Justice on Trial site catalogues many other such campaigns. There is no Test match at Headingley this summer when India come on tour but many prisoners reading about Davis's case must long for the sort of publicity that would attract the public's attention as he did.